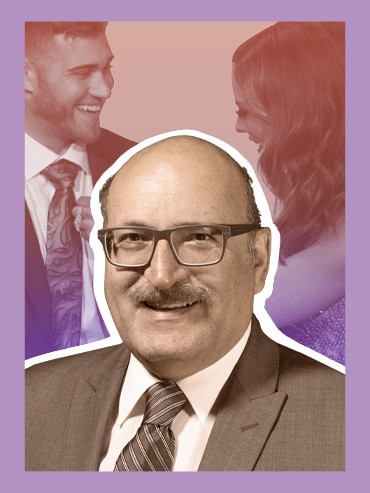

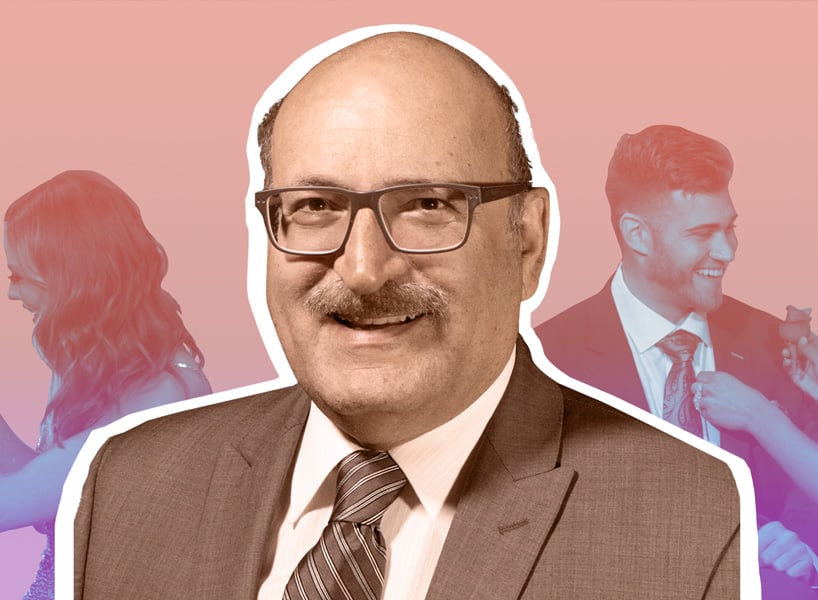

This TV Psychologist Helps Select Contestants For Reality Shows like The Bachelor

Dr. Steven Stein on what it’s like to help cast your fave (and least fave) contestants

Sometimes, reality TV stars capture hearts, but more often, they provoke scrutiny. Colton Underwood hopped a fence in Portugal to evade Bachelor producers during filming. Courtney Robertson mean-girled her way to the final rose (and a book deal) on Ben Flajnik’s season. And at a white tablecloth dinner, Real Housewife of New Jersey Teresa Giudice flipped a table during a screaming match with then-rival Danielle Staub. With each of these on-screen antics, viewers are left wondering, wine glasses held aloft—how do these people get on TV?

Enter: Dr. Steven Stein. While networks consult with lawyers and producers to assemble casts, many also refer to mental health assessments from Stein. As a clinical psychologist, he works behind the scenes to help cast and counsel the stars of our favourite guilty-pleasure shows. Stein, who’s based in Toronto and earned his Ph.D at the University of Ottawa, is an emotional intelligence expert with experience mitigating human crises for people engaged in active combat, counterterrorism and contrived drama. He’s consulted or provided psychological testing for the Canadian Forces, special units of the Pentagon and the FBI Academy (so, no biggie) and, more recently, for dozens of reality TV shows, including Big Brother Canada, the OG Survivor, The Apprentice and The Bachelor Canada. If there’s any common denominator to this work, Stein says, it’s stress, but the spectrum is wide. At one end is military deployment and physical danger, and at the opposite end is unscripted television where “the stress is more perceived.” Even with perceived stress, a lot goes into his job.

When tears flow and tempers flare on these shows, it can seem like reality TV producers just assembled a powder keg of personalities and lit the fuse, but the selection process is much more intricate. Stein interviews potential contestants and administers a battery of scientifically validated tests, including IQ and emotional intelligence assessments. Depending on the show, candidates could take up to seven of these tests, while Stein looks out for two things. “One is mental health issues, psychopathology. We want to screen out for anything serious, problems with addiction or anger,” Stein says. “The second part looks at actual characteristics, how they’re likely to behave in certain scenarios.”

Outward behavior and psychological safety make for a precarious balance. As awareness and conversations around mental health increase, producers still draw ratings with watchable, emotional and sometimes cringe-worthy contestant reactions, while Stein ensures all that drama isn’t detrimental to contestants’ health.

Casting has consequences

Apart from immunity and elimination, you might think there isn’t much at stake on reality TV, but casting is “a huge liability for networks,” says Stein. In a social media-saturated world, viewer judgement is omnipresent, and it can be pretty harsh. An entertainment news story last year counted nearly 40 reality TV deaths linked to suicide around the world since 1986. Last summer, the suicide of former Love Island contestant Mike Thalassitis, among other high-profile cases, prompted a UK government inquiry into reality TV and mental health. The hit show’s UK network added protocols, including social media training, to protect the well-being of its stars (none of these contestants worked with Stein). What audiences consider casual entertainment comes with grave psychological threats to the contestants. Stein’s job depends on an entertainment culture that pushes ordinary people to the brink—or over fences, or into the role of the villain—so others can watch. His role is to keep them safe.

Many people who volunteer for reality TV do it for the novelty of the experience, Stein says, and wind up having fun, or even launching careers. If handled safely, it can be a positive experience.

When choosing the perfect contestants, character traits are flexible and vary with each show. Is it a couples-based competition? A culinary throwdown? A revolving door of first dates? The ideal cast is a moving target. Some producers are looking for a mix of characters that Stein likens to “casting a Broadway play.” Exaggerated characters elicit reactions, even from the cheap seats, with John-Hughes era stereotypes. The jock. The prude. The weirdo. The villain. Though Stein’s would-be stars do tend to have one thing in common: “I would say 90% of the people I see score high on narcissism. If you’re shy or introverted, you’re not going to be good on reality TV.”

A dramatic exit?

Between the intensity of filming, long periods of downtime during production and close quarters for castmates often forced to live together, there’s bound to be an emotional emergency—or explosion. For that, Stein is on-call. During a crisis, he’s brought in to meet the contestant and help them decide whether to stay, “based on what’s best for their health in the long term.” Viewers have seen it all. A broken alliance, a moment of jealousy or the sheer stress of filming have caused plenty of on-screen breakdowns and early departures (and given us some truly iconic moments, like Ashley I’s cry face). But opting out could do more damage than staying to “work through the stress,” Stein says, adding that some of these former contestants have come back to him years later, thanking him for the chance to stay after a struggle. There are many reasons for self-elimination. Ali Fedotowsky left The Bachelor for fear of losing her job. Cassie Randolph dumped Underwood, uncertain about her feelings for him, leading to the fence-jump seen ’round the world. And Andi Dorfman left because Bachelor Juan Pablos Galavais was a grade A jerk. All valid reasons.

If contestants do decide to stick it out, they often endure more than just day drinking in mansions on their way to elimination and sponsored Instagram posts for Fit Tea, with stress triggers outlasting their time in the public spotlight. Post filming, these temporary celebrities might need to handle the comedown after a rapid dissent from fame or contend with a new public brand that follows them even after the cameras stop recording. Stein explains that some contestants are genuinely surprised to find that viewers have cast them as the villain, despite what they feel were good intentions.

“I have to prepare them for what’s going to happen once they get out in the world,” Stein says. “The fact that there are already people who can’t stand them, who hate them.” Hatred travels much further in the age of Twitter rants and viral news. Stein readies them to face the trolls, to “separate the role they play on TV with who they are as a person” by reminding them to stay grounded, and focus on family and friends—not the opinions of strangers.

Yes, some of it is real

Though the scenarios we see on-screen are contrived (how many real first dates include helicopter rides and costume changes?), contestant reactions are not. The most sought-after quality is authenticity. “We want real emotions,” Stein says of what audiences look for in their on-screen contestants, “That’s what people want to watch.” On The Bachelor franchise for instance, “there are people really looking for a partner.”There undoubtedly are others with ulterior motives (we’re looking at you, Juan Pablo), but Stein believes some contestants are sincere. They’ve tried everything else and really want to fall in love—especially with someone who’s already been vetted. The women on The Bachelor Canada tell Stein they feel better after his assessments of their potential love interest, “rather than a regular blind date, where nobody’s screened the characters.”

So what about those villains? As we all know from watching, villains do make it through, and not by accident. “We sometimes try to cast for villains,” Stein says. “People come in saying they want to be the villain.” (Talk about self-awareness.) “Some are reality TV junkies and they’ve seen all the shows. They identify with the villains and they believe they are that character.” And that’s fine, says Stein, as long as they aren’t phony. You can be a jerk, you just need to be honest about it (*ahem* Jed *ahem*). If not, sooner or later, someone will sniff out the act. Maybe it will be the viewers. Of course, Stein is thinking of them, too.

FLARE Archived Content

To see the original article, search for it on the Flare archive: https://flare.fashionmagazine.com